Juneteenth and the End of the Civil War

In most wars, the losing side officially surrenders to the winning side. For example, both Germany and Japan signed formal surrender documents at the end of World War II.

This did not happen at the end of the Civil War. The Confederate Government did not formally surrender to the Union. Instead, each Confederate Army did it’s own independent surrender.

Appomattox

In early April 1865, General Grant’s army broke through General Lee’s defenses after a ten-month siege around Richmond and Petersburg. The South abandoned both cities. Lee’s army fled westward, intending to unite it with the other main Confederate army in North Carolina. Grant aggressively pursued, finally surrounding the remnants of Lee’s army in Appomattox. Lee surrendered on April 9th. While commonly thought of as the end of the Civil War, other Confederate forces remained in the field still fighting.

Appomattox Campaign

Carolinas Campaign

North Carolina

Union General Sherman captured Atlanta in September 1864. He commenced his ‘march to the sea’ through Georgia, ending in Savannah, Georgia. From there, he launched the final campaign, marching north through South Carolina into North Carolina, attacking forces led by Confederate General Johnston. This campaign ended with the surrender of the remaining Confederate army on April 26, 17 days after Appomattox and 12 days after Lincoln’s assassination.

Texas

At this point, only scattered Confederate forces remained. As news of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and Johnston’s surrender in North Carolina spread, these Confederate forces surrendered to the nearest Union troops. Most of these occurred in early May 1865. In early June 1865, the last major group to surrender was the Confederate army west of the Mississippi in Texas and Louisiana.

President Andrew Johnson declared that the ‘insurrection’ had ended in June 1865.

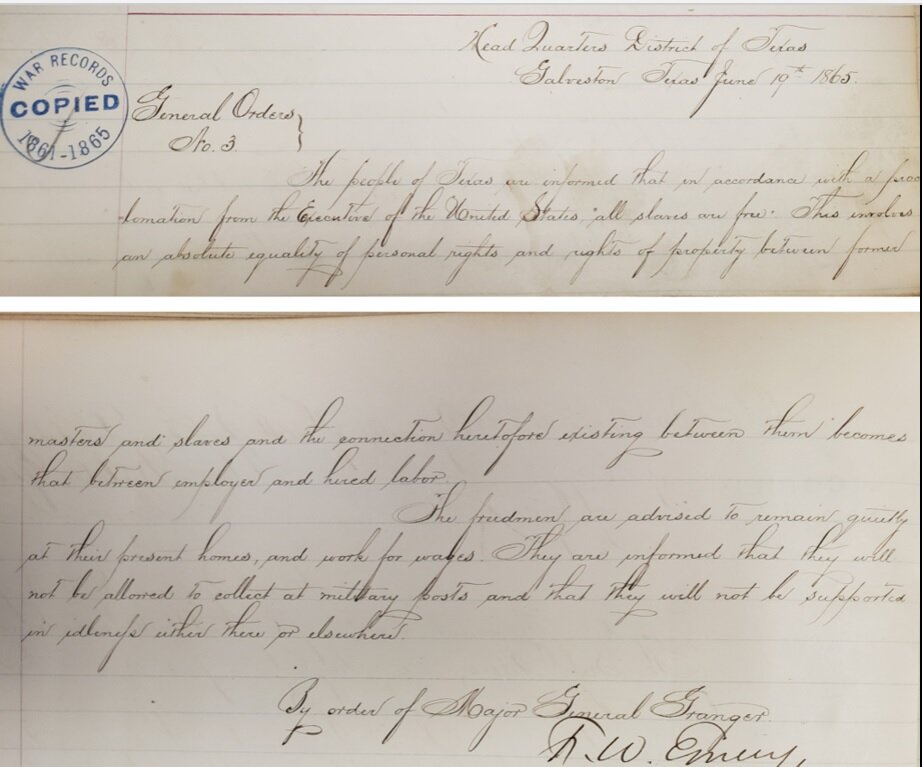

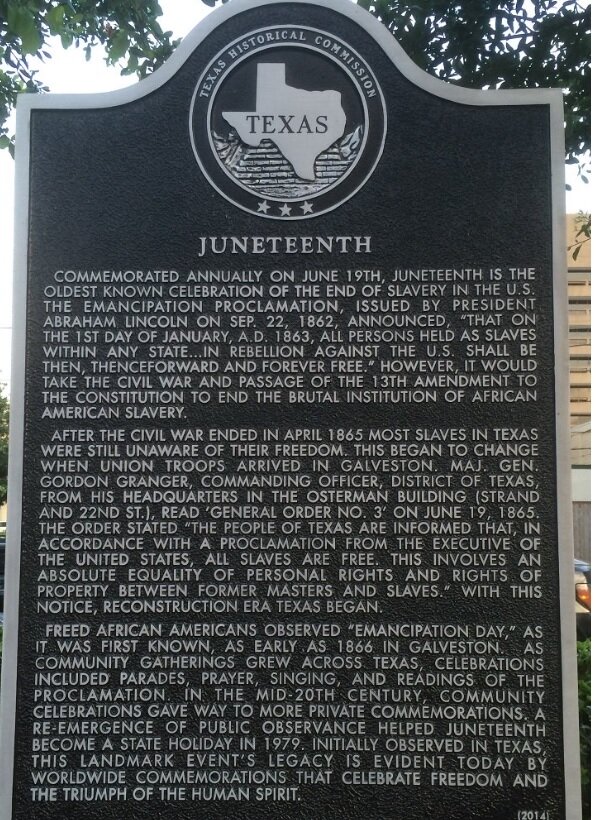

As Union armies conquered Confederate territory, they freed the slaves in those areas. Texas was quite remote in those days, with limited war action. As a result, few Union troops were available to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation, even though the war was over. Union general Gordon Granger arrived in Texas with a Union force and addressed the problem on June 19, 1865, while in Galveston, Texas. He issued this order:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

By order of Major General Granger.”

Celebrations began in Texas the following year, and slowly spread throughout the country. Over 100 years later, in 1980, Texas became the first state to declare June 19 an official State holiday. Many other States are starting to also recognize the date as the official end of slavery in the United States. It is now a National Holiday.

The day is alternatively called Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Liberation Day, and Emancipation Day. Now it goes by Juneteenth, an amalgamation of June and Nineteen.