The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

The country is bitterly divided. The President opposes policies supported by large majorities in Congress. Congress passes bills over Presidential vetoes but is concerned whether the Executive Branch will enforce those laws. The result, the 1868 impeachment and narrow acquittal of President Andrew Johnson. Is this similar or dis-similar to the current impeachment investigation?

Andrew Johnson was a Southern Democrat from Tennessee. He remained loyal to the Union after Tennessee, a slave state, joined the Confederacy. As Union armies occupied the state, Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor. In 1864 Lincoln replaced his first term Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin, with Johnson. Lincoln wanted to express unity by including a Southern Democrat, and he officially ran under the National Union Party ticket, mainly composed of the Republican Party.

Lincoln disagreed with Congress on Reconstruction of the South; how to rebuild the country after the Civil War ended. In December 1863 Lincoln issued a Presidential Proclamation creating the ‘Ten Percent Plan.’ The plan allowed Southern States to rejoin the Union and form State Governments if ten percent of the voters took an oath of loyalty to the Union and the State constitutions banned slavery.

Congress, with significant Republican majorities, felt the plan was too lenient. In the summer of 1864 Congress passed the ‘Wade-Davis’ bill. This bill provided for provisional military governors in the Southern States, a requirement that 50% of the voters take a loyalty oath, and banned high ranking Confederate officers and political officials from holding future governing positions. Lincoln ‘pocket vetoed’ the bill. (A pocket veto occurs when the President declines to sign a bill into law during the ten days after the law is passed, while Congress itself is not in session). Lincoln felt the bill too harsh and would encourage continued Confederate resistance.

Lincoln’s assassination occurred in April 1865, just a few weeks after his second Inauguration in March 1865. We do not know how President Lincoln would have handled reconstruction of the Union. President Johnson pardoned most Southerners and allowed them to set up State governments as they saw fit. Many Southern states passed laws known as the ‘Black Codes,’ which restricted the rights of the newly freed enslaved people.

Congressional Republicans passed several bills to support equal rights in the South. One created the Freedman’s Bureau, an agency to provide temporary housing, education, and support to African-Americans. The second, the Civil Rights bill of 1866 (“An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication”) guaranteed equality under the law. President Johnson vetoed both bills; Congress overrode both vetoes.

Voters rewarded the Republicans in the 1866 election, electing veto-proof majorities to Congress. With continuing resistance in the South, in 1867, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts. These laws provided for military governors over the South until the States created a state constitution guaranteeing universal voting rights, and that the state approved the 14th Amendment (equal rights) to the U.S. Constitution. Again Johnson vetoed the bill, and Congress overrode the veto. Concerned that the Supreme Court might rule some of the Reconstruction acts unconstitutional, Congress removed the right of the Courts to hear cases regarding those laws. Congress override Johnson’s veto of this bill also. Various explanations have been advanced for Johnson’s vetoes. These range from States’ rights to Constitutional concerns to racism. It may have been a mix of all three.

Congress was concerned that Johnson, as military Commander-in-Chief, would not enforce the Reconstruction Acts. Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, supported those acts. To protect Stanton from Johnson, Congress passed the ‘Tenure of Office Act.’ This Act prohibited the President from removing a Federal official without the approval of the Senate. Under the Constitution, Federal officials are appointed with the ‘advice and consent’ of the Senate. This bill would have extended the Senate’s powers to require its approval for removal of those officials. Again Congress overrode Johnson’s veto of the bill.

Notwithstanding this Act, Johnson went ahead and removed Secretary of War Stanton from the Cabinet. The Senate refused to ratify the removal. Johnson did not reinstate Stanton. As a result, Congress decided to impeach Johnson for violating the Tenure of Office Act. Congress passed eleven articles of impeachment against Johnson, most related to disobeying the act. The Senate trial started in March 1868.

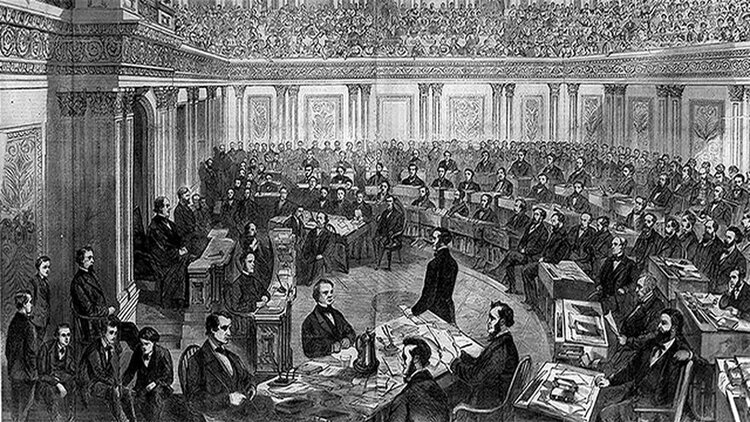

Andrew Johnson Impeachment

The Senate contained 54 members at the time. Conviction required a two-thirds vote or 36 Senators. 35 Senators voted in favor of conviction – Johnson survived by one vote, with a final tally of 35 in favor of conviction, 19 against. All the Democratic Senators and ten Republican Senators voted against, the 35 in favor were all Republicans.

Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas provided the final decisive vote against conviction. Ross was under extreme pressure to convict, but he resisted. Ross believed conviction would violate Separation of Powers and make the Executive Branch subordinate to the legislature. As he later wrote:

“ …the independence of the executive branch as a coordinate branch of the government was on trial. ... If the President must step down ... upon insufficient proofs and from partisan considerations, the office of President would be degraded, cease to be a coordinate branch of the government, and ever after subordinated to the legislative will. It would practically have revolutionized our splendid political fabric into a partisan Congressional autocracy”

President John F. Kennedy, in his book Profiles in Courage, described Ross as follows:

Ticket to view Impeachment

“In a lonely grave, forgotten and unknown, lies the man who saved a President,”and who as a result may well have preserved for ourselves and posterity constitutional government in the United States — the man who performed in 1868 what one historian has called “the most heroic act in American history, incomparably more difficult than any deed of valor upon the field of battle.”

The issue in 1868: Can Congress remove the President from office over policy differences? By one vote, the answer was no. Ironically, the ‘Tenure of Office Act’ was later held unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, meaning Andrew Johnson was impeached for violating an invalid law.

Partisanship is certainly one driver of the current impeachment process: both those in support and those opposed to the current impeachment investigation. As it was back in 1868.