Off with His Head

King Charles (I, II, & III)

Charles Philip Arthur George Windsor, the oldest son of the recently deceased Queen Elizabeth, is now King Charles III of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. He is a constitutional monarch with limited powers.

Monarchs used to have absolute power. The evolution to a constitutional monarch started over 800 years ago with the Magna Carta, which, among other clauses, required the King to seek parliamentary approval for new taxes. This series of entries covers the evolution of the British Monarchy.

Today’s King Charles (III) should hope for a better reign than the first King Charles!

Accession to the Crown and Marriage

Charles was the second son of his father, King James I. But his older brother died when Charles was 12, making him heir apparent. England was still experiencing religious conflicts between Catholicism and Protestantism. The country was officially under the Church of England, with traditional Catholic practices banned. Members of Parliament opposed his marriage to a French Catholic princess. Charles was crowned in 1626, but his Catholic wife refused to participate in the Protestant ceremony.

Off with his Head!

Following years of conflict with Parliament and two Civil Wars, King Charles was executed on January 30, 1649, 23 years into his reign. Parliament said he “hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented.” The legislature believed Charles “guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby.”

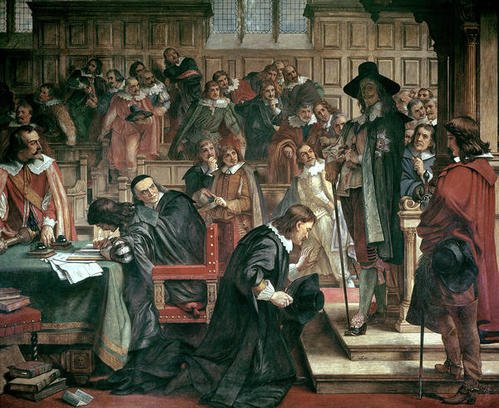

Parliament appointed a trial court. Charles refused to enter a plea, believing the Court did not have jurisdiction over a Monarch. He said he ruled by the “divine right of Kings.” He stated, “No learned lawyer will affirm that an impeachment can lie against the King ... one of their maxims is that the King can do no wrong.”

The Court appointed by Parliament found him guilty: “That the court being satisfied that he, Charles Stuart, was guilty of the crimes of which he had been accused, did judge him tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy to the good people of the nation, to be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.”

Before his execution, Charles said: “As for the People, truly I desire their liberty and freedom, as much as any whosoever; but I must tell you, that their liberty and freedom consists in having of Government by those laws, by which their lives, and their goods may be most their own. It is not for them to have a share in Government; that is nothing, Sirs, appertaining unto them. A Subject and a Sovereign are clean different things; and therefore until that be done, I mean, until the people be put into that liberty, which I speak of; certainly they will never enjoy themselves.”

The following events led to his execution:

Petition of Rights (1628)

The King believed in an absolute monarchy ruling by the ‘divine right of Kings.’ see above Parliament naturally saw it otherwise. Since the 1215 Magna Carta, only Parliament could impose taxes. To avoid this requirement, Charles imposed ‘forced loans’ on the country and imprisoned those who did not ‘loan’ him money. To support the army, he housed soldiers in civilian houses.

In response, Parliament passed the 1628 ‘Petition of Rights,’ protecting the individual against the state. This petition is still in force, and you may recognize similarities to portions of the U.S. Bill of Rights:

No taxation or forced gifts and loans without the consent of Parliament

No imprisonment without cause

No quartering or housing of military in private homes without the owner’s agreement

Although Charles agreed to the petition, he then dismissed Parliament in 1629 and proceeded to ignore the petition. He refused to call Parliament back into session for eleven years!

Personal Rule (1629 – 1640)

For the next eleven years, Charles ruled without Parliament. By 1640, King Charles was nearly bankrupt.

First and Second Bishops War (1639 – 1640)

Religious disputes continued during his reign over differences in religious practices. Charles tried to enforce Church of England practices on the Presbyterian Scottish Church. Scotland expelled the Anglican Bishops, leading to conflicts known as the ‘Bishops War.’ Charles needed funds and called Parliament back into session. Parliament refused to raise taxes, and Charles dissolved it after three weeks (known as the ‘Short Parliament.’). After the Scots defeated the English army in northern England, Charles was forced to sign a treaty allowing Scotland to continue its religious practices.

The Long Parliament (1641 – 1660)

Now out of money, Charles was forced to call Parliament back into session. Known as the ‘Long Parliament,’ it stayed in session for nineteen years.

First English Civil War (1642 – 1646) and Second English Civil War (1648)

Parliament passed bills restoring its authority against the King, who rejected them. These laws included:

1642 Militia ordinance claiming control of the militias.

“Nineteen Propositions” seeking a larger share in governance. One clause required Parliamentary approval of the King’s ministers and military leaders (similar to the U.S. Senate approving Presidential appointments).

The King attempted to arrest five leading members of Parliament. They went into hiding. War now erupted between forces favoring the King and those favoring Parliament.

Each side (Royalists or Parliament) won battles until Parliament created the ‘New Model Army,’ a professional force led by the central Parliament. This army defeated the Royalist forces, and King Charles I surrendered in 1846.

Negotiations between the King and Parliament failed because Charles refused to compromise his belief in absolute Monarchy. In 1648, war broke out again between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians. Parliament won.

Rump Parliament

The Parliamentary forces were split between those who felt a compromise with Charles was possible and those who opposed. Opponents of Charles resolved the split by using the army to remove supporters of compromise from Parliament. The reduced Parliament became known as the ‘Rump Parliament’ and voted to put Charles on trial for treason, establishing a ‘High Court of Justice’ to try him.

Aftermath

As we’ll cover in a future post, the execution of Charles did not restore peace.